Chapter V: Growth and Advocacy, Mid-1980s to Mid-1990s

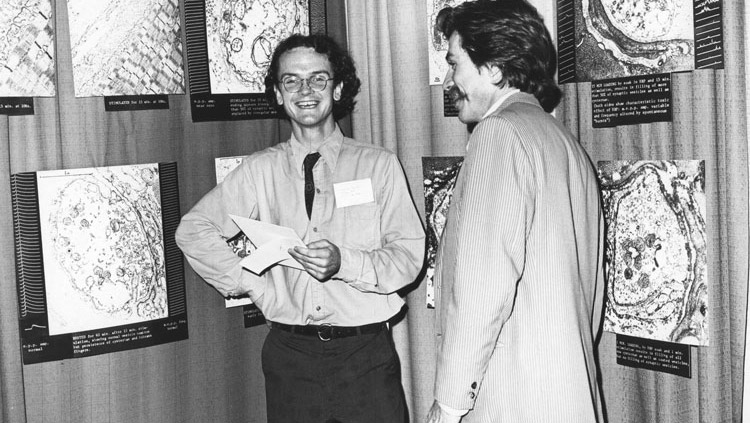

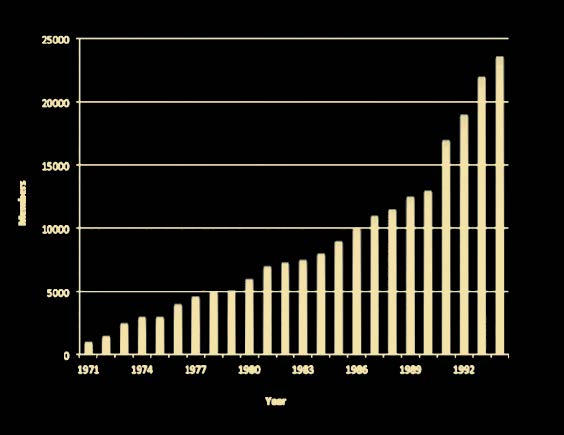

The Society flourished throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. Figure 27 charts attendance at the Annual Meetings from 1980 to 1994. As can be seen, the size of the meetings increased substantially each year except for a slight drop in 1994. The graph reveals a three-fold increase in attendance over those 15 years. SfN continued its significant growth during the 1980s, even as several more established biological societies experienced periods of stagnation. From 1979 to 1989, individual membership more than doubled from 6,351 to13,433, and the number of chapters grew from67 to 97.180 Neuroscience departments and programs flourished as well, increasing from29 in 1978 to 47 in 1986.181

The makeup of the field was also changing and becoming ever more diverse. In January 1982, more than 4,000 SfN members (60% of the total membership) responded to a membership profile questionnaire. This data provided some surprising information about the scope of the field: The vast majority (92%) of neuroscientists worked in at least two broad areas of neuroscience and received research support from a diverse array of government institutions. Approximately half of the field held positions at hospitals or at veterinary or medical schools, while 34% were affiliated with a university or college basic or social science department. The authors of the questionnaire had “greatly underestimated the breadth of departments,” listing only 50 choices. However, 376 members reported “other” as their primary departmental affiliation, citing “a profusion of departments ranging from Algology and Allied Health Therapies through Family Medicine, Kinesiology, and Marketing to Physiological Acoustics, Quality Sciences and Women’s Studies.” Non-primate mammals were the most common research organism (40%) studied by members, followed by humans (16%), vertebrates other than mammals (11%), and cell and tissue cultures(10%); only 9% were using non-human primates. Finally, it was not unexpected that, despite the Society’s interest in ethnic and gender diversity, 79% of the respondents were men, and 91% were white.182

The physiological psychologists, who saw their work in one of the oldest “brain sciences” as a bridge between behavioral and the newer molecular neuroscience, became concerned “that behavior and psychological processes were being relegated to a rather secondary status within the Society,” while the cellular, genomic, and molecular work dominated public and academic interest. A group of these researchers wrote an open letter to the Council in 1982, urging it to support better interdisciplinary education and to avoid polarizing the field.183 Five years later the group reported in Neuroscience Newsletter that they were continuing a series of “semi-informal meetings…where the topic of discussion was the direction of the neurosciences and the role that psychology will play in this new discipline.” When they analyzed their own participation in the Annual Meetings, and their collaborations with diverse colleagues, these researchers had found “a strong and growing relationship between physiological psychology and neuroscience. Subjective impressions of neuroscience as solely a molecular and reductionist discipline are not supported.”184

Funding Discovery

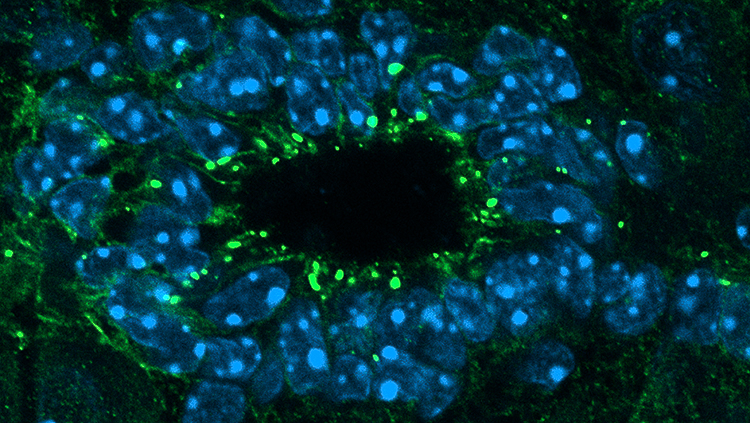

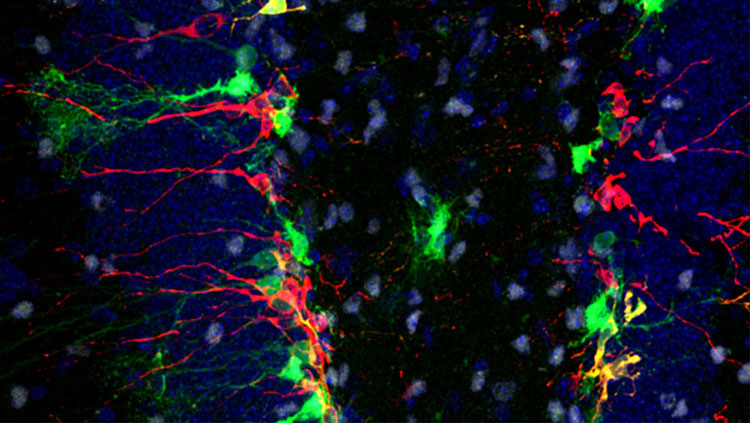

The important promise of neuroscience research is that it will unlock fundamental secrets about who we are as biological organisms and as a species whose intellectual capacities separate us from the rest of the biological world and about how we can correct the disabling neurological disorders that deprive victims of part or all of their human identity. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, some of the keys to those secrets appeared to be within reach, as fMRI and PET imaging opened up the study of human cognitive functions, even emotional learning, and laboratory technologies clarified the processes of neurogeneration and axonal outgrowth. At the molecular level, the field continued to be energized by breakthroughs such as the discoveries of the genes for Huntington’s disease and Duchenne muscular dystrophy and the elucidation of the biological substrates of Alzheimer’s and the spongiform encephalopathies. The use of methylprednisolone was one of the first steps toward improved rehabilitation of spinal cord injury victims.

Nevertheless, significant funding for the brain sciences has never been a forgone conclusion and has required major advocacy efforts on the part of individual scientists and of the Society as their premier organization. NIH has provided the bulk of biomedical research dollars over the past 50 years and supported the lion’s share of neuroscience research. NIH’s extramural grant program originated after World War II, when a small group of medical research grants was transferred from the Office of Scientific Research and Development to the still rudimentary institute. Under the leadership of Directors Rolla Dyer and later James Shannon, NIH evolved the peer-review mechanism to validate the distribution of its largesse as impartial and driven by scientific standards while using the same rhetoric and the memory of major scientific achievements such as penicillin and polio vaccine to obtain ever larger appropriations from Congress. Other federal agencies, such as NSF and the Department of Energy, followed its example, but NIH always led the pack. In the expansive era of the 1950s and 1960s, total NIH funding increased from $52 million to more than $1 billion.185 These grants built research laboratories, and funded young scientists to start their careers at universities allover the country. Although total appropriations never decreased in the 1970s and 1980s, the annual percentages of increase were reduced as successive Republican administrations called for fiscal restraint. As young scientists started their own labs and hired their own students, they found themselves in tighter competitions for fewer dollars. The Society quickly recognized the need to take a strong stance in focusing government attention on neuroscientific objectives and achievements to maintain, and if possible increase, the share of appropriated grant funds allocated to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Soon after Floyd Bloom became SfN president in November 1976, he learned that neuroendocrinologist David Hume's NIH training grants were in peril because of congressional budget cuts.186 An SfN poll conducted a few months later revealed that 95% of the membership received more than 50 percent of their research support from the federal government; for 82%, federal support constituted more than 80% of their budget. NINCDS contributed the bulk of the funding, while NIMH funded an additional 12%. “The data at hand clearly indicate that the funding for fundamental research is clearly inadequate for the pressure of the field and the growth of its research potential."187 The Institute directors were themselves members of SfN, and they also encouraged the Society to take a more active role. In June 1977, David Tower, the director of NINCDS, used the Neuroscience Newsletter to address a passionate plea for neuroscientists to articulate the political and social significance of neuroscience. In “Understanding the Nervous System: Man’s Last Frontier,” Tower exhorted his fellows to “engage intelligently at the interface between research and its application to the delivery of health care and services … [along the] continuum from the most basic, the most theoretical to the very practical human disease problems."188

Funding for Neuroscience

Bloom was already in action. He had sent an open letter to SfN members on March 29, 1977, asking them to contact the Senate and House Appropriations Subcommittees and express concern over the lack of funds for basic research. He encouraged them to describe their own work, and to explain exactly how a decrease in funding would “halt scientific progress.” Bloom also suggested that local chapters invite their members of Congress to attend a chapter meeting, to impress upon them the importance of neuroscience research and to foster a working relationship. These were the talking points: “The work we are doing is important, the quality and rate of progress in the neurosciences has never been greater, and to impair this process through illogical funding practices is intolerable.”189 SfN members responded enthusiastically, and reported that their letters had had “unquestionable impact” with congressional staff members.190

On April 19, 1977, Bloom and David Cohen testified before Joseph Foley, chairman of the National Committee for Research in Neurological and Communicative Disorders, part of the House Subcommittee on Appropriations for HEW/Labor. They expressed concern about “the erosion of federal support for neuroscience … at a time when research into the basic mechanisms of brain organization is in the midst of its most exciting and productive period.” Bloom and Cohen argued for the unique scientific and clinical importance of neuroscience, stressing that fundamental neuroscience research was the key to understanding neurological and mental disorders, which affected some 165 million Americans.191 This effort was successful, and the subcommittee recommended to the full Appropriations Committee that the NINCDS FY1978 budget be increased to $175 million, $14 million more than President Carter had requested.192 This represented a 15% increase for the institute, compared with a 12% increase for NIH overall.

The following year, Cohen took up the torch and reported to the SfN Council that, although he was heartened by “the reversal of the negative attitude towards basic research … [and] a thrust toward greater emphasis upon and support for fundamental science,” he did not foresee that FY1979 would be “a ‘bumper’ year for federal support for neuroscience.”193 The Council appointed Cohen, Bloom and Maxwell Cowan to an ad hoc committee on research resources, which was renamed the Governmental and Public Affairs (GPA) Committee in 1980.194 The committee’s charge was to maintain contact with the heads of the various funding agencies, to advocate with Congress to maintain or increase neuroscience appropriations and to encourage members to write letters and speak to their own legislators.

Government and Public Affairs

Cohen stressed the urgency and importance of their efforts, writing in Neuroscience Newsletter that “while we cannot look forward to a year of real prosperity [in FY1980], we can expect a year of reasonable support; unhappily this is not the case for the biomedical research enterprise as a whole… .Our efforts had a genuine impact on this year’s appropriations, and in this regard our thanks are due those Society members who contributed so valuably to educating our national legislators with respect to the importance of brain research.”195

Cohen, Bloom, and Dominick Purpura led the GPA Committee’s efforts through the 1980s. As SfN president in 1981-2, Cohen acted to formalize the committee’s advocacy efforts.196 After his presidency, the three leaders continued to devote considerable time to “Washington-watching,” petitioning lawmakers and testifying before Congress on appropriations for neuroscience research.197 They sounded again and again the call for help to the mentally ill and neurologically impaired and reminded their listeners of the promise of insights into human consciousness and behavior. Cohen regularly published updates on federal funding levels in Neuroscience Newsletter, and invited the directors of the relevant agencies, including NINCDS, NIMH, and NSF to use the newsletter as vehicle for communicating with the SfN membership. Because “legislative tracking [was] … a persistent, moment-by-moment task,” Cohen urged the Council to consider hiring a legislative aide as soon as the central office budget allowed for another staff person.198

The GPA Committee took advantage of the Society’s location in Washington, DC, to great effect and built coalitions with other groups with similar concerns, such as the National Committee for Research in Neurological and Communicative Disorders, NSF’s Interagency Working Group in Neuroscience, the American Association of Medical Colleges and the Inter-Society Council for Biology and Medicine.199 SfN representatives joined members of the Association of Neuroscience Departments and Programs each spring to visit members of Congress to discuss the importance of neuroscience funding, a program that by the 1990s was known as “Capitol Hill Day.” Although few lawmakers were in the city during the 1986 annual meeting, which was held in Washington immediately after the mid-term elections, the GPA Committee took the opportunity to sponsor special neuroscience education events for congressional staff members, in the hope that they would facilitate relationships with members of the legislature.200

This person-to-person activity relied heavily on a handful of active scientists and GPA members who were in easy commuting distance of Washington. But political issues with neuroscience implications could arise in any part of the country; in 1987, SfN launched a grassroots program to encourage more neuroscientists to inform and stay engaged with local politicians and the media.201 At the same time, Cohen, Bloom, Purpura, and their colleagues urged the Council to consider contracting with professional advocates; even the most politically savvy scientist could not always be attuned to unanticipated political problems or take the time to represent the Society’s needs.202 In 1989, SfN was one of 66 founding members of Research!America, a non-profit education and advocacy alliance of universities, professional organizations, foundations, and medical manufacturers that works to make health-related research a higher national priority.

Decade of the Brain

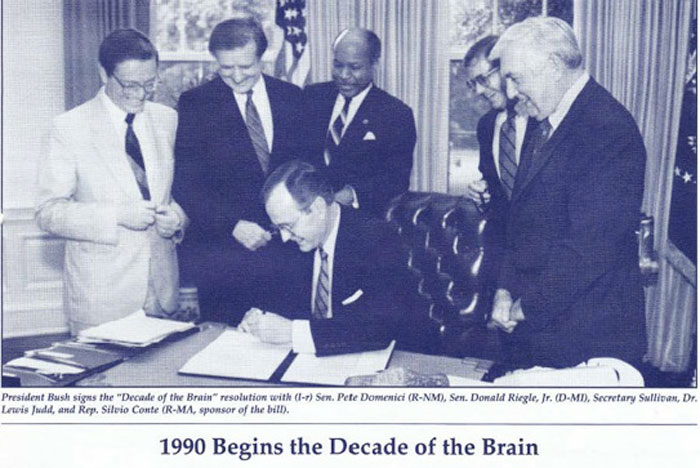

The GPA Committee’s crowning achievement was to gain federal recognition, of the importance and value of neuroscience through the proclamation of the “Decade of the Brain,” which they hoped would be attached to major funding increases. In 1987, the National Coalition for Research in Neurological and Communicative Disorders (NCRCD) invited the GPA Committee to collaborate with an NINDS Advisory Council on a proposal that would “set forth basic science and clinical research priorities and establish a framework for a multi-year effort to capitalize on the tremendous progress in brain and nervous system research in recent years.”203 This proposal persuaded Representative Silvio Conte and Senator Donald Riegle to introduce legislation to significantly increase neuroscience funding. At the hearings on the bill, Purpura offered oral testimony on behalf of NCR and SfN. After outlining the most significant advances in treatment of neurological diseases, he warned that recent significant budget cuts would force the scientific output of the United States to fall behind that of other countries.

He urged Congress to support the “Decade of the Brain” initiative, not only to “improve the quality of life for countless millions who suffer from neurological disorders,” but also because “neuroscientists are persuaded that understanding [the] brain as the organ of mind and the source of our humanity is the highest priority that humankind has for its own survival.”204 In July 1989, President George H.W. Bush signed a joint congressional resolution designating the 1990s as the “Decade of the Brain.” (Figure 28)

Decade of the Brain

For SfN, the Decade of the Brain (DOB) was an affirmation of the advocacy work of the Government and Public Affairs Committee, and an impetus to strengthen its existing relationships with lawmakers. It was also the perfect occasion for a series of public events showcasing the importance of neuroscience. The Council created an ad hoc DOB Committee to coordinate a Decade of the Brain Symposium for members of Congress every spring, to be followed by a “Capitol Hill Day” of congressional office visits.205 At each symposium, SfN would honor appropriate members of Congress with a DOB award for their support of neuroscience. Honorees included Rep. Silvio Conte (1990), Rep. William Natcher (1991), Sen. Ernest F. Hollings (1992), Rep. Steny Hoyer (1993), Sen. Pete Domenici and his wife Nancy Burk Domenici (1994) and Rep. John Porter (1995). Meanwhile, SfN contracted with Frankie Trull, founder and president of the Foundation for Biomedical Research, to coordinate SfN’s contacts in Congress and with other government agencies and policymakers.206 In 1995, SfN’s Public Information Office began publishing Brain Waves, a quarterly bulletin for congressional health aides, to communicate “the far-reaching impact of neuroscience research and … the Society’s interests to policymakers and other significant lay audiences."207

The Decade of the Brain became a powerful rhetorical tool when urging legislators to increase science funding. Purpura invoked the DOB’s promise twice in testimony before the Senate Appropriations Committee, asking how the president could put his political weight behind such an initiative, even if fiscal necessity forced him to propose cuts in relevant NIH funding. In 1990, he reminded lawmakers that “collective willingness is not enough” and dramatically predicted that if there was adequate research support, then the Decade of the Brain could be “a prelude to the Century of Man, in which humankind will be emancipated from the dread of disability and the stigma of dehumanization that attends dissolution of the human spirit in dementia.”208 His 1991 testimony described the neuroscience community in equally vivid language as “thousands of superbly trained investigators prepared to answer the most important question of the Cosmos — How does the Brain Work?” and insisting that the Decade of the Brain mandated “a level of support that no single health sciences’ institute or agency can provide within the current framework of appropriations.”209 A proclamation was not enough; neuroscientists needed secure support if they were to deliver on the promises of the Decade of the Brain. Despite the publicity, significant increases in NIH funding for neuroscience did not materialize until relatively late in the Decade, when the NIH budget doubled under President Bill Clinton, thanks to efforts led by Senators Arlen Specter and Thomas Harkin.210

Neuroscience Literacy

In the early 1990s, SfN also launched a new series of public education initiatives focused intensely on the benefits of neuroscience research, thereby ensuring that the voting public would continue to fund neuroscience even after the Decade of the Brain was over. As SfN President Robert Wurtz explained in 1991, “The concerns of many of us in the Society now extend beyond communication within our science to the survival of our science….Two interacting issues require our attention: the attack on the use of animals in research and a level of funding that lags the growth of neuroscience….The solution to these problems requires long-term effort: the education of the public on the methods, achievements, and benefits of neuroscience.”211

In April 1989, for the first time, the Council approved a proposal to ask members to contribute $5 for a special Public Education Fund in addition to their annual dues.212 This income would support a professional director of public education, who would be responsible for preparing scientific material for lay audiences and for coordinating publicity at the annual meeting and throughout the year.213 Within six months, more than 90 members had contributed over $2000 toward the program and the Council was confident enough in the new initiative to hire an experienced science writer.214 The new director produced Brain Facts, an educational booklet on basic brain and nervous system anatomy for science reporters and the public; regular updated editions followed and electronic and audio versions have been added to the SfN website (culminating in the BrainFacts.org website in 2013). He also worked closely with the Committee on Animals in Research to produce special materials for elementary and high school teachers on the importance of animals in research.215

The ad hoc Committee on Secondary Education initiated a working partnership with National Association of Biology Teachers (NABT) to train high school biology teachers in neuroscience methods and develop supplemental curricula on the brain. NABT members received copies of Brain Facts and SfN representatives attended the NABT annual meeting to discuss specific issues of animals in research and teaching.216 In April 1991, the Council signaled its support for these programs by designating the ad hoc committee as a standing Committee on Neuroscience Literacy.217 The 1991 and 1992 meetings in New Orleans and Anaheim included “Education Day Workshops” on how to talk to children in schools and how to talk to the media.218

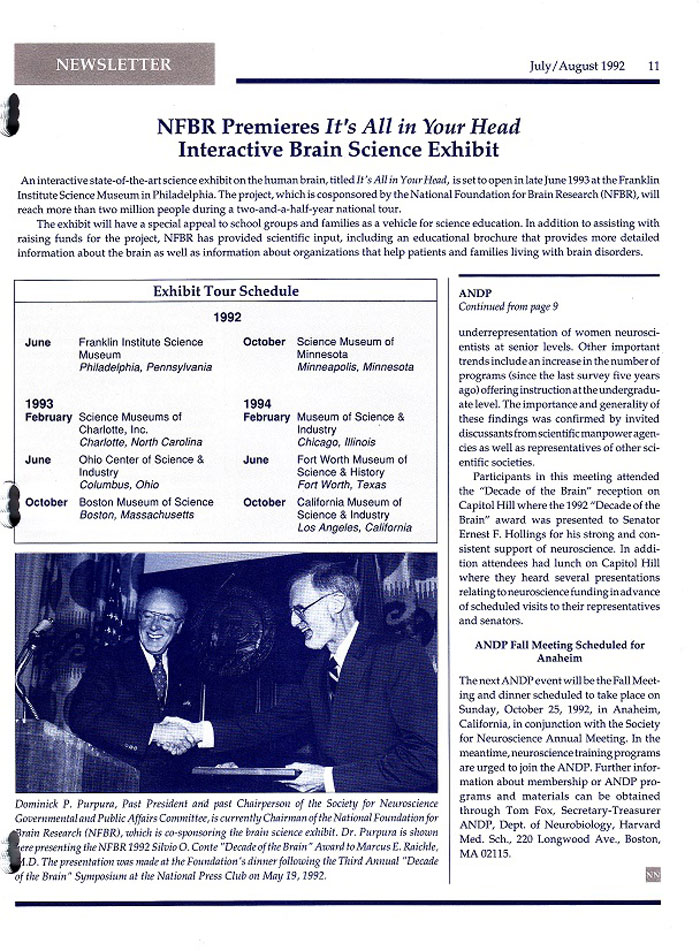

SfN also worked closely with other institutions and organizations on educational programs.

The Society co-sponsored a traveling exhibit titled “It’s All in Your Head” developed by the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia (Figure 29)219 and partnered with the Dana Alliance for Brain Initiatives (Figure 29) to reach a larger adult audience for its educational programs.220

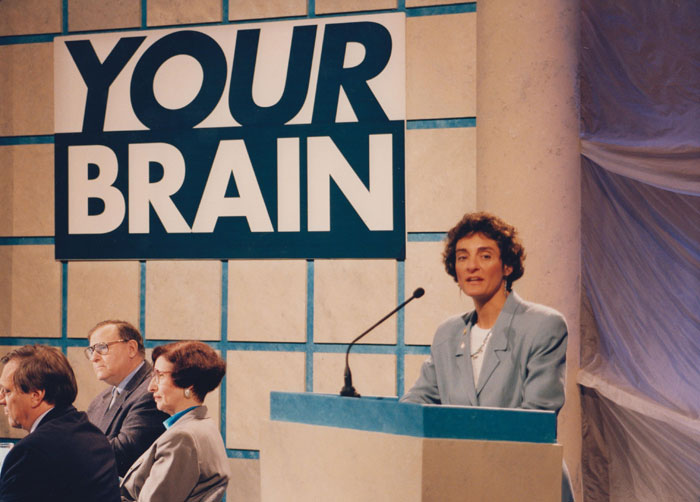

Dana Alliance

SfN President Carla Shatz opened the Alliance's "Brian Fitness for Life" Forum at the Salk Institute (See Figure 30) during the 25th Annual Meeting in 1995.221 Ray Suarez of National Public Radio moderated the panel discussion on brain development and adaptation that took place before more than a thousand attendees and was recorded for broadcast by WHYY, a PBS station in Philadelphia.222

The forum proved to be a highly successful public event that laid the foundation for Brain Awareness Week (BAW), first celebrated in May 1996. SfN members participated in over 200 events during the first BAW “national media blitz” and the Society quickly became part of the “core” of the Dana Alliance’s BAW partnership, with the potential to reach more than 25 million people each year.223 Bruce McEwen (President 1996–97), who had helped to develop the 1995 forum as a Council member, was particularly impressed with the Dana Alliance’s “town meeting” style programs.224 He saw BAW as a way to “enliven” SfN chapters and focus the Society’s educational programming and chaired the Brain Awareness Steering Committee for several years.225 SfN staff and leadership invested significant time in BAW planning, hosting a large introductory gathering at every Annual Meeting after 1996 and providing a Brain Awareness Toolkit to interested members.

As it expanded its outreach to government and to the public, one of the biggest challenges facing the Society in the mid-1990s was the demand to “go digital” rapidly to keep pace with the dramatic rate of technological change in communications, publications, and research practices. SfN overhauled its website in October 1996 to include resources for members and for the general public; and, for several years, the print Neuroscience Newsletter included a “Getting Caught on the Web” feature that encouraged members to use the online resources.226 In August of that same year, The Journal of Neuroscience went online on a trial basis, transitioning to regular digital publication in January of 1997; JoN was the second biomedical publication to have full-text articles available online.227 The processes of submitting abstracts, scheduling sessions, and creating the Annual Meeting schedule also began the transition to digital during this period, as did the Neuroscience Newsletter.

‘Celebrating 25 Years of Progress’

What did the Society for Neuroscience look like as it reached its silver anniversary in 1995? Its membership had exploded, making it one of the largest scientific organizations in the world. Following the first decade in which 5,000 members had joined the Society, SfN had grown nearly fivefold over 15 years, to 23,000 (See Figure 31), including many scientists working outside North America.228

Membership Committee Chairs Michael Zigmond and Israel Hanin and President Larry Squire proposed another membership survey, the first since 1981, to collect demographic data and understand current needs, as well as to help SfN plan for the future by identifying problems or barriers in training and research. The Membership Committee obtained NIMH funding for a two-part survey in 1995–96; the second part was a detailed statistical sample focusing on career development and issues facing women and minorities.229 Some interesting changes were reported by the 75% of members who responded: 20% identified as underrepresented minorities (up from9% in 1981), 30% were women (up from21% in 1982), and one-third were working in countries outside the U.S. The median age had increased from 37 to 41, with the largest group between 35 and 49. This figure did “not necessarily reflect an aging in the profession, but may indicate that membership now appeals to scientists in a broader range of disciplines,” a statement supported by the broad range of primary research interests identified by members. Moreover, students and postdoctoral researchers now accounted for 29% of SfN membership.230

SfN membership growth reflected the expansion of funding support and training programs in neuroscience. In 1968, an estimated 238 doctoral dissertations had been awarded in neuroscience-related fields. Less than a decade later, in 1976, U.S. biological science departments graduated 521 PhDs inneuroscience.231 By the early 1990s, American and Canadian institutions were awarding about1,000 PhDs per year in neuroscience relatedfields.232 SfN had played an important role in the creation of neuroscience departments and of interdepartmental programs that offered PhDs specifically in neuroscience. In 1978,there were 29 interdepartmental neuroscience programs; by 1986, this number had increased to 47.233 The growth of these programs led to the creation of the Association of Neuroscience Departments and Programs (ANDP) in 1981 to help develop curricular standards for graduate programs and track their development.234

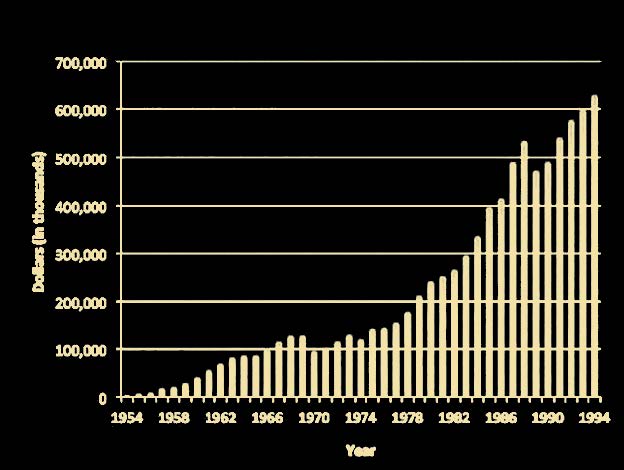

The dramatic growth of the field would not have been possible without the rapid expansion of federal finding, another area in which SfN leadership proved especially critical. Federal funding for all biomedical research grew at an unprecedented rate following World War II. But while the rise in federal funding for neuroscience mirrored this larger content, SfN leaders had helped to convince Congress of the importance of directing funds toward neuroscience. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) budget from the 1950s through the 1990s (See Figure 32) illustrates the results of their efforts.

One would be hard pressed to imagine these gains without the advocacy of SfN and its Government and Public Affairs Committee, exemplified by Dominick Purpura’s 1990 prediction that, if Congress provided neuroscientists adequate funding, “Humankind will be emancipated from the dread of disability and the stigma of dehumanization that attends dissolution of the human spirit in dementia.”235

Inside and outside the scientific community, neuroscience flourished and commanded respect. The American Association for the Advancement of Science established a Neuroscience Section in 1994 that quickly grew to one of the largest section sat their annual meeting. Authors and readers consistently regarded The Journal of Neuroscience as a prestigious place to publish and undergraduate students began to flock to neuroscience as a major. In 1991,SfN members established the Faculty for Undergraduate Neuroscience (FUN) as a separate organization to help instructors and students take advantage of the resources at the Annual Meeting.236

In addition, educational materials such as Brain Facts, Brain Concepts, Brain Waves, and Brain Briefings reinforced the message that SfN was the best source of reliable information about brain research for the public and particularly for lawmakers. Finally, the Society had developed a deep volunteer leadership pool by 1995, thanks to an active nominating committee that drew from the 20 working committees organized to address the priorities and changing needs of the organization.

SfN President Carla Shatz chose the theme “25 Years of Progress” for the 25th anniversary meeting in November 1995. On the first night of the meeting, fireworks lit San Diego Bay “to mark the virtual explosion of discoveries that has characterized the past 25 years of neuroscience” and the concurrent growth of the Society, which now encompassed a rich, diverse, and ever-growing set of subdisciplines and research approaches within a single field.237

The Society for Neuroscience established and ensured the disciplinary unity of neuroscience by facilitating communication of novel approaches and techniques while maintaining a clear focus on the brain and behavior; although it began as the U.S. affiliate of IBRO, SfN had transcended its American origins by welcoming members from around the globe. The emphasis at the 25th anniversary celebration was on how the Society had changed and matured to serve the needs of its members from creating formal and informal communication opportunities at the Annual Meeting to creating an integrated publication resource in The Journal of Neuroscience to making the case to Congress for the recognition and funding of neuroscience research to creating a meaningful public face for the neuroscience enterprise. But, with the organization rowing in size and scope, and the status and visibility of neuroscience in international science and culture expanding as well, SfN was about face significant new challenges as the 21st century dawned.

Related

Endnotes

- “Society Membership Continues to Climb.” NN 20:5, p.1.

- Zigmond, Michael J, and Linda P Spear. "Neuroscience Training in the USA and Canada,” n. 95.

- William Hodos, “A Profile of the Society for Neuroscience,” n. 102.

- Eliot Stellar and Alan Epstein, “Open Letter to the Council.” NN 14:2, March/April 1983, p. 2.

- Hasker P. Davis, Carol Elkins and Mark R. Rosenzweig, “The Role of Physiological Psychology in Neuroscience.” NN 18:1, January/February 1987, p. 6-7.

- http://www.nih.gov/about/almanac/appropriations/part2.htm. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- Interview with Floyd Bloom, May 6, 2014.

- “Federal Support of Neuroscience Research in 1977: Preliminary Results of Membership Poll.” NN 8:2 June 1977, p. 5.

- David B. Tower, “Understanding the Nervous System: Man’s Last Frontier.” NN 8:2, June 1977, p. 6-8.

- Open letter to SfN Members from Floyd E. Bloom, March 29, 1977, SfN Archive.

- “The Funding of Neuroscience Research and Training.” NN 8:2, June 1977, p. 1.

- “Statement of Prepared Testimony by Floyd E. Bloom, M.D. and David H. Cohen, Ph.D. Representing the Society for Neuroscience in Testimony before the Subcommittee on Appropriations for HEW/Labor House of Representatives 95th Congress, 1st Session, April 19, 1977.” NN 8:2, June 1977, p. 2-6; original in SfN Archive.

- “Last Minute News of Success.” NN 8:2, June 1977, p. 3.

- David H. Cohen, “Commentary on Neuroscience Funding Prospects in FY 1979.” NN 9:1 March 1978, p. 2.

- Council Minutes April 1980, and November 9, 1980, p. 9, SfN Archive.

- David H. Cohen, “Neuroscience Research Support for FY 1980.” NN 10:3 September 1979, p. 1.

- Minutes of 27th Council Meeting, October 22, 1981, SfN Archive.

- David H. Cohen, “All’s Well that Ends [Almost] Well.” NN 14:2, March/April 1983, p. 1; David Cohen interview May 22, 2014.

- David Cohen, “Government and Public Affairs Committee 1983-4 Report to Council,” p. 1, GPA Files, SfN Archives.

- David H. Cohen and Joe Dan Coulter, “Governmental and Public Affairs Committee 1982 Report to Council.” NN 14:4, July/August, 1983, p. 2-5; Government and Public Affairs Committee 1985 Report to Council, and Government and Public Affairs Committee 1986 Report to Council, GPA Files, SfN Archive.

- David Cohen, “Governmental and Public Affairs 1986 Report to Council,” GPA Files, SfN Archive.

- This action was to support both the GPA and the Committee in Animal Research, see discussion in text.

- Floyd Bloom, “Governmental and Public Affairs Committee 1988 Report to Council,” GPA Files, SfN Archive.

- Murray Goldstein, “The Decade of the Brain: Opportunities and Challenge.” NN 21:1, January/February 1990, p. 3.

- Dominick Purpura, “Oral Testimony, NINDS, April 25, 1989, Public Witness for NCR and Society for Neuroscience.” GPA Files, SfN Archive.

- “Society Holds Decade of the Brain Symposium.” NN Volume 21:3, May/June 1990, p. 1.

- Council Minutes April 27, 1995, p 10; Frankie Trull was Vice President for Government Affairs at Capitol Associates, and then started Policy Directions, Inc. NN 26:1, January/February 1995, p. 3 and NN 26:4, July/August 1995, p. 7.

- “Society Expands Outreach Initiatives.” NN 26:5, September/October 1995, p. 1, 5.

- “Purpura Testifies on Neuroscience Appropriations.” NN 21:3, May/June 1990, p. 4.

- Dominick Purpura, “Statement of Dominick P. Purpura, M.D. for the Society for Neuroscience Concerning FY 1992 Appropriations,” April 19, 1991, p. 2, GPA Files, SfN Archive.

- Robert Pear, “Medical Research to Get More Money from Government.” The New York Times January 3, 1998. www.nytimes.com. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- Robert W. Wurtz, “Report from the President.” NN 22:1 January/February 1991, p. 1.

- Minutes of Council Meeting April 15, 1989, p. 6, SfN Archive.

- Edward Perl, “Society Launches Expanded Program in Public Education.” NN 20:4, July/August 1989, p. 4.

- “Public Education Program Receives Generous Contributions.” NN 21:2, March/April 1990, p. 5.

- “Council Approves Public Education Initiatives.” NN 21:1, January/February 1990, p. 4.

- David Friedman “Society for Neuroscience and National Association of Biology Teachers Forge a New Relationship.” NN 22:2, March/April 1991, p. 1-2; Council Minutes April 17, 1991, p. 2, 4, SfN Archive.

- Council Minutes April 17, 1991, p. 2-3, SfN Archive.

- “New Events for Education Day in New Orleans.” NN 22:5, September/October 1991, p. 1; J. G. Collins, “Workshop for Secondary School Students Proved Successful.” NN 23:2, March/April 1992, p. 1-2.

- Council Minutes April 29, 1992, p. 13, SfN Archive

- Council Minutes November 13, 1994, p. 6, SfN Archive.

- “SfN Members Reach out to Public during Brain Awareness Week” NN 27 (March/April 1996): 1–2.

- “Public Forum Draws Standing Room Only Crowd.” NN 27:1, p. 19.

- “SfN Members Reach out to Public during Brain Awareness Week” NN 27 (March/April 1996): 1–2; “Brain Awareness Week Meeting Draws Large Attendance” NN 28 (January/February 1997): 1, 13.

- Council Minutes April 18, 1994, p. 5-6, and Council Minutes November 17, 1994, p. 7, SfN Archive; Israel Hanin, “Committee Prepares Membership Survey.” NN 26:2, March/April 1995, p. 4.

- Interview with Bruce McEwen, November 4, 2018, p. 6; “Celebrating the Success of Brain Awareness Week” NN 29 (November/December 1998): 4.

- R. Cliff Young, “Society Web Site Gets Facelift,” NN 27 (November/December 1996):1–2.

- Sol Snyder, “What Makes for Prestigious Publishing” NN 27 (November/December 1996):5,11; “Trial Period of Online Journal Comes to an

End Access Becomes Exclusive Privilege of SFN Members” NN 28 (January/February 1997): 3. - Society for Neuroscience, “SfN Membership Growth Graph,” Catalyzing Change in Our Environment: FY2007 Annual Report, p. 20.

- Council Minutes April 18, 1994, p. 5–6; Council Minutes November 17, 1994, p. 7; Israel Hanin, “Committee Prepares Membership Survey”

NN 26:2, March/April 1995, p. 4. - “Early Results of the 1995 Membership Survey.” NN 27:5, September/October 1995, p. 6.

- Marshall, Louise H. “Maturation and Current Status of Neuroscience: Data From the 1976 Inventory of US Neuroscientists.” Experimental Neurology 64, no. 1 (1979): 1–32.

- Zigmond, Michael J, and Linda P Spear. “Neuroscience Training in the USA and Canada: Observations and Suggestions.” Trends in Neurosciences 15, no. 10 (1992): 379–383.

- Cohen, David H. "Coming of Age in Neuroscience." Trends in Neuroscience (1986): 450-452

- ANDP, established as a separate organization, focused on the development of resources to extend and improve graduate and professional training in neuroscience. As part of its mission, it carried out periodic surveys of program characteristics, faculty, student diversity and financial support. ANDP would merge with SFN in 2009; see Chapter X.

- Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, U.S. Senate, 101st Congress, 2nd Session, on H.R. 5257. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. (1991): p. 191.

- Julio J. Ramirez and Larry Normansell, “A Decade of FUN: The First Ten Years of the Faculty for Undergraduate Neuroscience,” available at

funfaculty.org. - “Celebrate 25 Years of Progress at the Annual Meeting.” NN 26:3, May/June 1995, p. 1; Carla Shatz, “25 Years of Progress and Beyond.” NN 26:6, November/December 1995, p. 1, 15, 18.